The accelerated pace at which satellites are being launched into space has now drawn attention to some of its unintended consequences. In the process, a new sub-industry in the space sector is emerging.

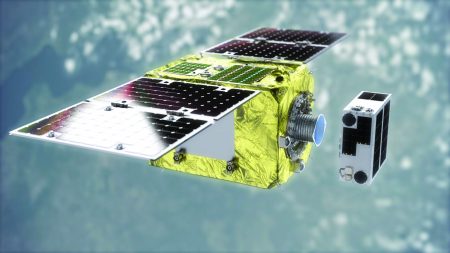

Over the past year, Japanese startup Astroscale has been testing its End-of-Life Services by Astroscale-demonstration (ELSA-d) technology, to show how man-made objects can be serviced and space debris can be removed from low-Earth orbits (LEO).

The two spacecraft that comprise ELSA-d – a 175kg ‘servicer’ and a 17kg cubesat ‘client’ equipped with a magnetic docking plate – were launched into a 550km LEO orbit in March last year. In August, the company said ELSA-d had successfully released and recaptured the client multiple times, offering early proof of concept. Although irregularities stalled the mission earlier this year, Astroscale is set to resume it soon and is learning valuable lessons about satellite servicing operations in space, the company said in a statement.

Astroscale is also working on several other on-orbit products. Its ELSA-M spacecraft, based on an evolution of ELSA-d’s technologies, is being created to tidy up non-magnetic satellite debris of up to 800kg at altitudes of 1,325km in a single mission. The Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan (ADRAS-J) craft, selected by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, will show how large-scale debris can be taken out of orbit. And its Life Extension In-Orbit (LEXI) mission will provide life extension and manoeuvring services to satellites weighing up to several thousand kilos in geostationary orbit (GEO).

“We expect that Astroscale will become a critical service provider for safely removing defunct objects from space and pioneering new ways to service, upgrade and transport spacecraft to maintain and grow the viability of Earth’s orbits,” Ron Lopez, President & Managing Director at Astroscale’s US arm, tells Satellite Pro.

The tech firm is among the early movers in a developing high-tech garbage disposal industry. Since the USSR launched Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite, space has become increasingly crowded. As of January, there were 4,852 active satellites currently in orbit, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), a science non-profit. But there are also more than 3,000 inactive orbiters above our heads. More than two-thirds of all satellites are in LEO, which requires the lowest energy for satellite placement.

In addition, millions of pieces of space junk circle the Earth. The result of explosions, collisions or anti-satellite tests, these debris are both working and defunct pieces of spacecraft or satellites, including discarded rocket stages, fragmented hardware and even paint flecks.

According to NASA’s Orbital Debris office, at least 25,000 of these objects are larger than 10cm across, while another 500,000 are particles between 1 and 10 cm in diameter. There are more than 100 million particles larger than 1mm. Of these, the US Space Command actively tracks more than 40,000 objects in space to avoid collision risks.

NASA puts the aggregate weight of material in orbit around Earth at 9,000 metric tons. This junk travels at speeds of up to 17,500mph, fast enough for even a relatively small piece of orbital debris to damage a satellite or a spacecraft. With debris constantly in motion, even communications or navigation systems here on Earth could be rendered in-operational by crashes and collisions.

As the frequency of such collisions increases, more space junk is being created. In theory, the result could be the Kessler Syndrome, a chain reaction of collisions making it difficult to launch new space missions, scientists warn.

“If we don’t do something within the next few decades – 50 years at most – then the Kessler Syndrome will become a reality. The youth of today will certainly need to solve the problem,” says author and space debris expert John L Crassidis, Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at the University at Buffalo, who works with NASA and the US Air Force on the issue.

In April, an international team of researchers writing in the Nature Astronomy journal highlighted another potential problem, warning that a dramatic rise in space debris will impact a wide range of fields, including astronomy.

“Modern society is completely dependent on services from space,” Lopez says. “Communications, financial systems, navigation, weather and national security warnings, and climate and environmental monitoring are all powered by satellites. The orbits these satellites occupy around Earth are becoming dangerously crowded.”

“While satellite operators and launch service providers have evolved approaches that remove satellite and spent upper stages from orbit at end-of-mission, this larger active and retired satellite population, and the more crowded orbital environment it will create, will drive future debris volumes unless we take proactive steps to manage the space environment. If the projected trillion-dollar-plus space economy is to be realised, it must be built on a more sustainable foundation. On-orbit servicing is that foundation.”

“While satellite operators and launch service providers have evolved approaches that remove satellite and spent upper stages from orbit at end-of-mission, this larger active and retired satellite population, and the more crowded orbital environment it will create, will drive future debris volumes unless we take proactive steps to manage the space environment. If the projected trillion-dollar-plus space economy is to be realised, it must be built on a more sustainable foundation. On-orbit servicing is that foundation.”

This could generate $14.3bn in revenue through 2031, he adds, citing Northern Sky research.

An exponential increase in the number of launches in this golden era of space exploration is only going to exacerbate the problem. Some 17,000 new satellites are set to be launched through 2030, research from Euroconsult shows. That’s a four-fold increase from the 3,800 sent into orbit over the previous decade, thanks to economies of scale in satellite manufacturing and a strong decrease in launch prices. Of the 170 constellation projects assessed, 110 are by commercial companies, often called New Space players. OneWeb, Starlink, Gwo Wang, Kuiper and Lightspeed represent 58% of these new launches.

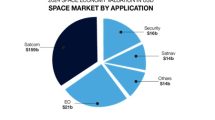

Besides defence and aerospace, IT and telecom provide the most significant revenue opportunities over the short and medium term from this pie in the sky. In particular, satellite broadband internet is in greater demand, with the global economy increasingly underpinned by connected technologies such as the internet of things (IoT).

The space economy is projected to be worth $1tn or more in 2040, up from $350bn at present, according to estimates by Morgan Stanley. Government space programmes continue to dominate the sector, accounting for three-quarters of current revenue at about $240bn, but even here the playing field has become more diversified. McKinsey data shows that around 70 countries now have established space programmes, including the UAE, Costa Rica, the Philippines and Rwanda.

Even without this increase in launch rates – in a business-as-usual scenario – the number of space debris objects greater than 10cm could double in the next 50 years, according to projections by the European Space Agency (ESA).

The ESA is the first space agency to commit to debris neutrality. By 2030, it hopes to be adding zero net debris to the Earth orbital environment, and by 2050 it hopes to have fostered a circular economy in space by using in-orbit servicing to ensure long-term orbital sustainability – in other words, to recycle, repurpose and reuse satellites and other man-made space objects.

In 2025, the agency hopes to be the first to remove an item of debris left in orbit. Its Clearspace-1 mission will deploy an experimental four-armed robot to bring back a 100kg Vega Secondary Payload Adapter (Vespa) from an orbit at about 800km, left there in 2013. The $104m project, carried out by Swiss startup ClearSpace, will work to match the velocity of the object before capturing it and bringing it back down into the atmosphere, Chief Engineer Muriel Richards told Newsweek.

Clearing debris is one approach to the problem. Another is refuelling, which could extend satellites’ lives, meaning fewer new launches. At present, satellites reach the end of their useful life when they run out of fuel. Many must be decommissioned at that point because there is no way to refuel them easily.

San Francisco-based Orbit Fab wants to enable permanent jobs in space and is currently building out the propellant supply chain to support that vision. CEO Daniel Faber tells SatellitePro how his “gas stations in space” will operate: “We will have fuel depots, big simple tanks of fuel that we launch on any available rocket, and reusable fuel shuttles that can take the fuel from the depot to operational satellites.” This reusability allows the company to amortise its costs over many deliveries.

In June last year, Orbit Fab launched the first fuel depot to LEO. Tanker 001 Tenzing stores the green propellant high-test peroxide (HTP) in a sun-synchronous orbit to refuel other spacecraft. It hopes to launch a similar depot to GEO this year. Its first two shuttles could be in orbit by 2023.

“We have had quite a lot of interest from both companies and governments interested in the refuelling and what it can do to their capital costs, such as moving CapEx to OpEx, as well as introducing mobility and flexibility to the business model, which has previously never been possible in the space industry,” Faber says.

Orbit Fab won a $12m contract from AFWERX and SpaceWERX, the US Air Force and Space Force innovation hubs, to integrate its Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface (RAFTI) with Department of Defense spacecraft for on-orbit refuelling missions. RAFTI is a high-tech refuelling system valve comprising a service valve and alignment markers. The company is also working with Astroscale on its new Life Extension In-Orbit (LEXI) Servicer spacecraft.

Several other startups have entered the space with proposed life extension and debris monitoring and clearance services. In India, five-year-old startup Manastu Space has created a satellite propulsion system that uses affordable green fuel. It has similar plans to offer refuelling services in space, Indian media report. Portuguese startup Neuraspace raised €2.5m in March for its AI-powered space debris monitoring platform. The solution aims to enable safe and sustainable in-orbit operations in the New Space economy.

Other proposals are looking at repurposing larger objects into small-scale space stations, sending objects at the end of their lives into a graveyard orbit where they are unable to interfere with most space travel and existing satellites, or using the debris as a source of fuel, Crassidis explains.

Taking a comprehensive approach is SpaceLogistics, a US satellite-servicing firm owned by Northrop Grumman, with solutions for repair, recycling and refuelling operations. Rob Hauge, President, SpaceLogistics, tells SatellitePro how the company is working on several space sustainability projects aimed at enhancing and extending satellite life.

Taking a comprehensive approach is SpaceLogistics, a US satellite-servicing firm owned by Northrop Grumman, with solutions for repair, recycling and refuelling operations. Rob Hauge, President, SpaceLogistics, tells SatellitePro how the company is working on several space sustainability projects aimed at enhancing and extending satellite life.

“SpaceLogistics is the only company providing in-space servicing today, with our two Mission Extension Vehicles (MEVs) which are extending the lives of two Intelsat satellites. Our second-generation vehicles, known as Mission Extension Pods (MEPs), will be installed by our Mission Robotic Vehicle (MRV). The MRV and MEPs will continue to reduce the need to build new satellites by extending and enhancing those already in orbit.”

SpaceLogistics’ MEVs are the company’s first generation of in-space servicing spacecraft and were designed to extend the life of satellites running low on fuel. Its MEPs, set to launch in 2024, will similarly extend the life of client satellites. The MRVs that install them will also provide on-orbit augmentation, inspection and repair capabilities.

“In addition, the MRV will also be the first commercial satellite designed with robotic arms to be flexible to serve as a multi-mission platform to also enable inspection, repositioning and repair of client satellites. The MRV and MEP programmes have completed their preliminary design reviews, the first robotics arm has been assembled, the first test of the MEP capture mechanism has completed, and first light has been achieved with the Hall Current Thruster (HCT) for the electric propulsion system,” Hauge says.

In February, SpaceLogistics sold the first MEP to Optus, an Australian satellite telecommunications major. By 2025, the company hopes to take refuelling a step further with Mission Refuelling Pods (MRPs) and active GEO debris removal. By the end of the decade, it wants to be manufacturing and assembling spacecraft on-orbit.

“On our horizon is enabling the eventual repurposing and recycling of what is already on-orbit, to make space truly sustainable,” says Hauge.

The US recently became the first country to announce a ban on missile tests against space satellites, but the scale of the problem requires more than individual approaches, something the global community seems to realise.

The US recently became the first country to announce a ban on missile tests against space satellites, but the scale of the problem requires more than individual approaches, something the global community seems to realise.

The United Nations published guidelines concerning space debris in 2010, the start of what has been called a highway code for space. Last June, the leaders of the EU and the G7 group of nations – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the US and the UK – agreed to focus on the development of common standards of sustainable operations, as well as space traffic management and coordination.

Now momentum is building around the Net-Zero Space Initiative, aimed at actively reducing orbital debris. Yet, resolving the issue needs more action. “We need to have all countries agree to these common guidelines, which hasn’t happened yet,” Crassidis says.

Add Comment